How a solution turned out to be a problem.

On 16 January 2023, the Mumbai dailies carried the news of a man whose throat was slit by a kite string. The tragedy occurred on Makar Sankranti, the day of the winter harvest festival, when colourful kites do battle in the skies. Nylon kite string, called ‘Chinese manja’, is stronger than traditional cotton but banned in the city due to its potential for harm. Sanjay Harare was riding his bike on an elevated road when a nylon kite line from a nearby rooftop gusted towards him. His throat cut, he lost control of his bike, swerved into a side wall and soon died.

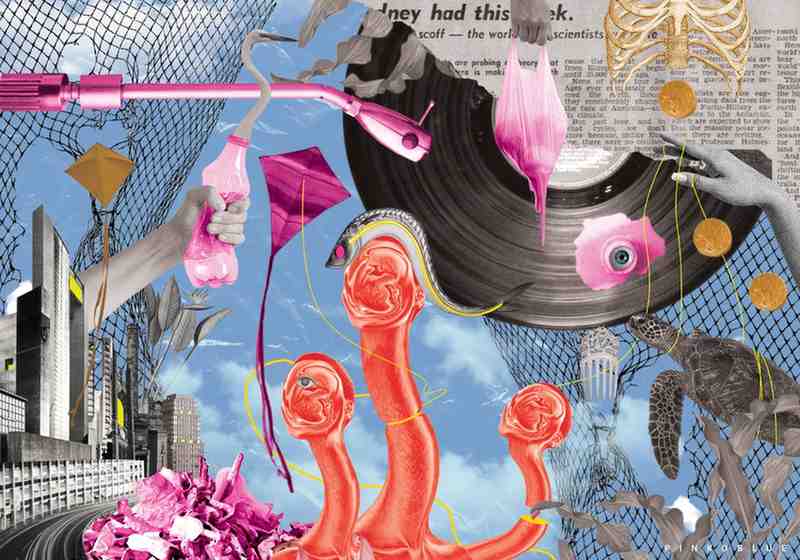

The incident is an apt metaphor for the power and peril of plastic, that seemingly innocuous material that pervades every part of our lives. The invention of plastic made modern life possible. It made a variety of goods affordable for a large population, democratising consumption. But the material also helps ravage the earth and perhaps our bodies.

The irony is that when plastic was first invented, it was seen as an environmentally friendly alternative to finite natural materials; a way to preserve wildlife from extinction. Advertisements from the late nineteenth century for combs of celluloid, one of the first synthetic materials, touted the saving of thousands of elephants and tortoises. Until then, combs were traditionally made of shell and ivory, and the latter was also used to make billiard balls. The next big invention in plastic was bakelite, made of formaldehyde and phenol, and it too replaced another scarce and natural substance—shellac, made from the excretions of the lac beetle.

Once humans found ways to make new versions of this malleable chain of carbon molecules, we never stopped. The story of the twentieth century can be told through each new invention: vinyl, the sound of our fathers’ record players; nylon, the slink of cheap stockings; formica, the kitchen counter of the 1950s; Teflon, the joy of the novice cook; thermocol, the children’s party plate; Tupperware, to give food to our neighbours (and get some back); polythene, the fabric that shrink-wraps our lives; and, inevitably, the unquenchable PET bottle.

Today, we know the true cost of this convenience.

Plastic litter has been an issue for decades, as anyone who has hiked up to a hilltop only to find a carpet of bottles knows. And we’ve known about plastic in the sea since 1997 when yachtsman Charles Moore discovered the Great Garbage Patch of plastic in the Pacific Ocean. But scientists have only recently been learning more about the pestilence of microplastics, the millions of tiny particles that are accumulating on ocean floors. They’ve even found polyester microfibres in the distant Arctic Ocean, washed down from the laundry machines of Europe and America. The tiny fibres are ingested by fish, disrupting their digestive and endocrine systems, and are entering our food and water systems. Microplastics have been found in beer, honey, sugar and salt.

We eat plastic every day—and drink it too.

Because plastic is made from petroleum—it was oil companies like DuPont that helped invent new plastic materials—it is also part of the climate change problem. The fashion industry’s love for cheap polyester and other synthetics generates the greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet.

Smart people have been looking for fixes ranging from better garbage collection systems to more recycling. None of these solutions have worked well so far. Some are trying to make plastic easier to destroy, inventing new versions that are degradable, compostable or at least more recyclable. What no one wants to talk about is the non-technological fix: producing and consuming smaller amounts of the stuff. Or, in the case of a kite-flyer, not using it at all.

Decades ago, marine biologist Rachel Carson, writing about another useful chemical that turned out to be lethal for wildlife, said that humans would be challenged, as never before, “to prove our maturity and our mastery, not of nature but of ourselves”. In an era of hyperconsumption and environmental collapse, the motto ‘Less is more’ is not an aesthetic choice or even a political position. It is a survival imperative.

Cover Image: Dipanshu Singhall